Tick, tock. Tick, tock.

Watching the second hand turn, slowly spinning effortlessly, endlessly. Continuously.

It’s never ceasing. Well, as long as you take care to keep it moving. A watch, with only a seldom swipe of the index finger and thumb across the crown, twisting the stem to wind the mainspring through a series of gears. Inching forward, pushing us through time.

Time. Craig came to quickly understand that you can out-think situations, outwit people, outrun options, but you can’t do anything to outlast time. It always wins.

Always.

That first year in prison, the change was tremendous. Unstructured, uninterrupted life on its own, any way you want to live is supplanted with sequestration, rigidity and harshness. There was little room for solitude. Unless, just unless you could get away from it all. Walk away, run even, through the yard, past the gates, beyond the reach of the guards, inmates, crazies, convicts and castoffs, into another world.

The world of a book was the only solace available. And Craig quickly took up the pastime with fervor. He read an average of one novel per month in 1995 in addition to his regular mail, monthly magazines and periodicals. Twelve books, a total of 4,626 pages. It wasn’t just to get away. He always had a thirst for knowledge, a questioning of ‘Why, why is that like that?’ In his current circumstance and situation, it may have been more to his detriment than not to be so questioning. Taking it inside the covers, reveling in the author’s otherworld made for a perfect way for him to kill time and cure his insatiable curiosity.

As I was debating how to start this chapter, I began Googling random words I had written beside a part of our conversation which I thought was particularly telling. I wasn’t sure how to connect it, how to string his meaning, his solely unique understanding along to the outward emancipation of his feelings with any type of eloquence. These indiscriminate words and partial thoughts helped, descriptors for a situation understood by one man alone:

Loneliness.

Island of torment.

Reflection.

Caring. And uncaring. Simultaneously.

Distrust.

Unforgiving.

Given over.

As these words tumbled through my head and out my fingers onto the keyboard, I could only think of the human connection. The connection to humanity that he lost the minute he committed murder. Thrown away, tossed to the side whether he knew it or not. Sitting in a cell or hanging out in his bunk, he had little chance of meaningful connections with intelligent, warm human beings.

Or did he?

Searching ‘human connection quotes’ I came across one that said: “Human connection is the most vital aspect of our existence. Without the sweet touch of another being we are lonely stars in an empty space waiting to shine gloriously.”

It was a poem attributed to Joe Straynge. I have no idea who that is, so I typed that into the search box. But as luck or divine providence would have it, or just as the world said it should be, my fingers got mixed up and entered ‘Joy Straynge human connection quote’ which isn’t quite the same, unless Joe has a secret side.

The fourth image that popped up caught my attention. It was a graphic with a musty-looking picture, grainy, hand drawn with the quote “Dark times reveal good people” and the author’s name “Remarque.” I’m not all that cultured, not quite refined. I don’t go reading tons of books from the early part of the 20th century, so it didn’t have meaning with me. A little more sleuthing led to some simple facts: it was from a book called ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’ written by a former German soldier in World War I named Erich Maria Remarque. Part of the Wikipedia reference said, “The book describes the German soldiers’ extreme physical and mental stress during the war, and the detachment from civilian life felt by many of these soldiers upon returning home from the front.”

Interestingly, and I did not know this at the time I was searching the interwebs, this book was the final novel that Craig read in Year 1 of his stay at camp.

Dark times are not easy, in war or prison.

I wondered about this often when I thought of Craig over the years. How was he making do? Was he really getting along as well, being as well-adjusted as he sounded in his letters? Is there chance he’s lying about his situation and it’s worse than we can imagine? What’s the chance he is actually making prison life – doing time – actually as easy as it looks from the picture he paints? Those weren’t questions I thought I’d ever get answered, until he came home. When he was back, I realized he pretty much did. He made it work. Got through, keeping his head down unless the time required him to stand up. Got through, staying in his lane and focusing on his goal. Got through by removing himself from the situation whenever he could, sometimes to another world through his books.

Sometimes, though, you get removed without having a choice in it. That happened too, at least once.

It was after we had half a dozen or so conversations, getting a little deeper into how things really worked, and I asked what I thought was a simple question: when was the loneliest time?

Nothing.

It was like the other end of the phone line went dead. Pure silence. I could hear that tick, tock, tick, tock in my head, along with my breathing. I could barely, almost imperceptibly, hear his breathing. I don’t know how long it lasted, but the quiet went on long enough to be unsettling, making me almost squirm wondering what could have happened, what might have pushed him back into his own mind as it was easy to tell he was lost in a thought, one I wasn’t sure he was going to share.

Finally, he said, “That, that is a good question.”

Another significant pause. And then he started to come back, rejoined the conversation as he normally had.

He was in Yuma when it happened. He created a substantial faux pas, those were his exact words, on his part that put him on the outs with everyone. It went on for months. It was, he said, pretty lonely, pretty much the whole time. The hard part is dealing with others who you come to congregate with, ones who may be like you personally. The understanding is everybody is doing their own number, their own prison sentence, and if you get too involved in their life, you do their time too and yours is enough.

After another pause, he said, “I really couldn’t afford to get emotionally involved or invested in anybody because people got moved randomly at any time. So if your well-being is attached to this individual and they get moved, you get crushed and don’t have them anymore. So everyone is kind of an island.”

More silence.

“And for me personally I’ve always been comfortable being by myself. I don’t like being alone, but I can be comfortable.”

How so? He circumvented his loneliness with letter-writing. His thought was that you had to write ‘em to get ‘em. It was a mind-set change. When he first went in, he’d write a letter when he feel like it. And most letters are then responded to. About 4-5 years in, the realization that these people took time to write one and they deserve to get a response of some kind finally set in. So he set it upon himself to answer every single letter received. He also had a quota: 10 letters a month. Sunday was letter-writing day, his day set aside for that task. He’d write 2-3 letters every Sunday. When you set a schedule for yourself, it motivates you to do it and after a while, it becomes a habit. You work it into your schedule and before you know it, you schedule around it.

When he was on the outs with everyone, the timing was easy to get his writing done. But it begged a question: what’d he do to get on the outside? What was the faux pas?

Let’s let him explain:

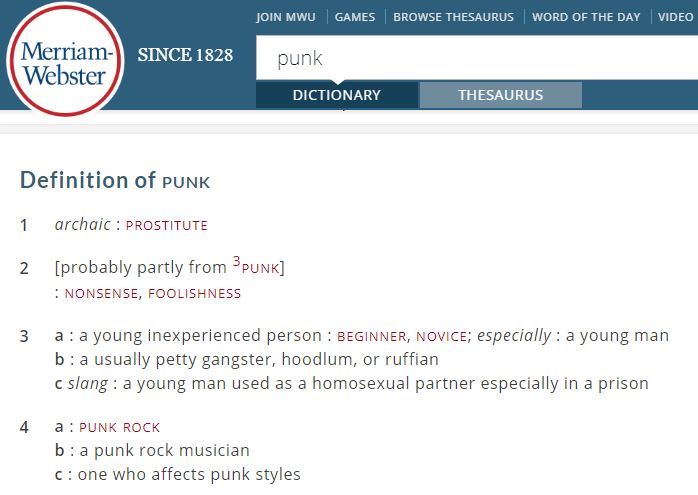

“In Arizona, one word that does not get used across all races is ‘punk.’ Do not call anyone a punk. Webster’s definition is: a young ruffian, and the second definition is a useless person. Using the word punk was the worst slur anyone could say to anyone.

“I was in the double bunk bed, I had just got there. And the guy I was bunkmates with was a piece of shit. Two people live in 42 square feet of space. So, it was one of those situations where there’s a fine line where you live with someone, like with a wife. What’s mine is mine and yours is mine, but some things are exclusively hers. The same goes for you. You live with someone who, you’re shoved together and would not ever choose to live with, you can’t completely say, I mean you can, but you can’t say, ‘This is all my stuff, so don’t touch it and I don’t touch yours.’ You can do that but then you’re the asshole.”

It was pretty obvious in our conversations that that — not being an asshole and getting on the outs with people, especially a cellie — was always the goal. If it turned into a bit of a snit, then being that petty about stuff, it would lead to none of the other social considerations being reciprocated to you. That left you on an island as well. So you always try your best to accommodate, even if you might not always want to, simply because it could come back on you down the road if you don’t.

“If someone is cooking, 3-4 guys will pitch in a bunch of food to make a stew or something. Well, the social conduct is, if there’s four of you cooking in your bed space and the guy next to you is indigent, he has no money, nothing to eat, nothing extra, well, you’re sitting eating in front of him. You can’t cut him off, so ‘Here, grab a bowl man. Get some.’ He doesn’t have any money to put anything in but you give him charity, somebody who is without. Those that have, should kick down to those who don’t have any. If you’re the kind of person where this is all mine, I’m not going to share with anyone, then no one will share with you. One hand washes the other. That even intensified living in a small area with bunkmates. Most of the stuff is my stuff, but we’ll share some stuff. I had a TV, and he didn’t. We would both watch my TV. I’ve always been a big kool-aid drinker. So you’d hear him, ‘Can I get a . . . ?’ Usually it’s cigarettes, coffee, something. So can I get a coffee or a kool-aid? The only thing I asked, I have no money, I’m not working yet, just don’t eat all my stuff.”

It’s pretty obvious what’s coming next, right? You already know.

“Well, this asshole does.”

And there it is.

“The Country Time Lemonade container, there are three flavors, and he helps himself. Day after day after day, he gets down when I’m mixing some for myself and he mixes for himself. He goes to the store, buys his cigarettes, coffee, chips, but no drink mix. The first jar was down to 1-3 servings, and then next to nothing. He would not drink it all, as he’d leave a little in the bottom of the jar. You can see where this is going. So I cut him off, like, ‘No you don’t get any more of my stuff, you drank all of it.’ He says, ‘No I left some in it.’ We go back and forth, back and forth, because his charity was getting cut off. I don’t have a job and you’re eating all what you buy and half of mine. I’m living off savings because I don’t have a job. So I cut him off. I think I took my TV back too. Put it on my TV stand, not his where we can both watch it. It pissed him off, so he could not watch for free.

“We have words and he calls me a punk. Well, you’re a fucking idiot, I don’t care what you think. I didn’t swing on him. They’d put me in (the hole) probably. The people in charge come over and say ‘You can’t let it slide. You can’t let it slide. He called you a punk. We can’t have you here if you don’t call him out.’”

That right there, even us on the outside know, that can’t be a good feeling when “one of the people in charge” comes over. There has to be a pit in your stomach, a tightness in your breath, pounding in your head maybe. Uneasiness in general, and a tenseness as your guard has to be on the highest alert at that time. It was for Craig as he had to figure out what to do. There wasn’t really any choice other than to do what they wanted.

“You really can get in a fist fight without getting caught. Other white guys on the run who demanded it happen — saying either you get in a fist fight and beat his ass or you’re moving out, which means protective custody, which means we beat your ass — well, they get a spade game going. They are standing in the vision of the officer, and of course they get in a loud card game and talk shit back and forth. It’s raucous. The officer, he looked over and ignored, because of the noise they make to cover the fist fight I was in. He just laughs.”

The commotion wasn’t unusual. Neither was the fact that it was a cover for something illegal. Every illicit act had a cover, whether in the public domain or in dark corners out of sight. The fact that he did it, went through with the fight and put himself on the level he was expected to live up to, you would think that’d be enough. That they’d let it go. But there’s a unique logic that plays out in prison, in a way we may just have to scratch our head in disbelief.

“A fist fight was acceptable to the powers that be, because (they think), ‘You handled business, now you can stay.’ Because I didn’t swing on him immediately when he called me a punk though, that put me on the outs with a bunch of the whites. ‘Oh, he doesn’t stand up for himself, blah, blah, blah.’ Which for me, I don’t really care what you say about me because I know who I am. We see this a lot in modern social media. Someone called me a name. I’m damaged, so I’ll sue you for $1 million for hurt feelings.

“Not swinging on him as soon as he called me a punk, I was put on the outs. I was an outcast for a few months, until one guy who I was friends with before, he distances himself from me and then after a few months, we started talking a little bit. ‘I had been watching you, and you’re exactly the same before, during, and after that event and that’s why I’ll hang with you. You didn’t allow the social stigma to change who you are. You’re the same person as before, not being blown around by social opinion. You stayed true to yourself. You called the guy a punk idiot anyway.’”

All of that time away, time apart from anything resembling a normalcy for the confines he was in, that had to take a toll, even if Craig felt comfortable with it. Like everything else, he could break it down, see it for what it really was, objectively, but it didn’t matter. All that mattered was the ‘group think’ and what the leaders on the yard thought. Whether it made any sense at all was a completely different story.

“The social inconsistencies where image and appearance override logic and absolute truth, and once the fad passes, no one really cares. That in a nutshell is some of the absurdity of the thought process that is required in a prison setting. It also goes into that kind of absurdity which will make you feel crazy. This makes no sense, no logic, I mean there’s logic but it’s a skewed logic, where left is right and right left and up is down, it’s topsy-turvy. When you speak to an individual in the community, they will, most of them anyway, will admit it’s just a fucked up way of doing things. But as a group, they support it.”

Thus finding a little time to get lost in a book every now and then, outside of the group, away from the discombobulated logic was the only way to find solace and, in some sense, sanity. And he had plenty of time on his hands to read.